The history of the Northeast is often interwoven into Gerry’s work and sometimes the full significance of a piece is only revealed by unraveling the story behind it.

The lands we now call New England were not discovered by Europeans, as English-American history teaches but were inhabited by groups who simply referred to themselves as “the people.” This region was vital to their identity because they lived from its resources and saw themselves as caretakers of the land. One group living in southern New England referred to themselves as “The People of the First Light,” the Wampanoag. It was upon their ancestral home that the Pilgrims first settled and numerous conflicts with the lands’ original inhabitants ultimately led to the most disheartening of these: King Philip’s War.

Pometacom, Metacom, or Metacomet, three of many variations of his name, is better known as King Philip. He was a Wampanoag Sachem (chief) and a celebrated figure in early New England history. To this day, more than three hundred years after his death, he is considered by many Indian people to be a patriot – one who endured the loss of his ancestral lands, family, friends and ultimately his life for the freedom of his people.

After he was killed in 1676, his body was quartered and hung from trees; his hands and feet were severed and displayed by the colonist as trophies of war, and his skull impaled on a pole in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where it hung for a generation. The message was made clear to Indian people that this was now the fate of those who would not submit to the rule of Plymouth.

By 1675, European encroachment into Wampanoag territory had pushed Philip and his people to a small peninsula of land known as Consumpsit Neck (today called Mount Hope Neck in Bristol, Rhode Island). A series of incidents culminating with the death of the Indian John Sassamon, led to hostilities between the Wampanoag, who were determined to reclaim their ancestral home, and the English who were expanding their colony. This conflict became the last great struggle of the indigenous peoples of southern New England to retain their lands and maintain the lifestyle of their ancestors.

With winter coming on, Philip sent hundreds of his tribe’s women and children into the neighboring Narragansett territory for protection. When authorities in Plymouth learned this, they gave the Narragansett’s an ultimatum: turn them over to the English, or the United Colonies would view this as open hostility towards them. The Narragansett knew the fate of Philip’s women and children should they turn them over to the colonist, as many Indian captives were sold into slavery, in the West Indies, to defer the English cost of the war. So the Narragansett did not relinquish any of their guests.

In December 1675, a company of about one thousand colonial soldiers under the command of Governor Josiah Winslow of Plymouth, marched deep into Narragansett territory and discovered the Natives hidden on a small island in what is today Kingston, Rhode Island. In the John Carter Brown Library in Providence, Rhode Island, is a poignant account of the events that transpired that day, written by a colonial participant just nine days after the event. It states: “We were no sooner entered the fort… that we fired about 500 wigwams and killed all that we met with of them, as well as squaws and papooses. Our enemies began to fly and ours had now a carnage rather than a fight, for everyone had their fill of blood. It did greatly rejoice our men… to see their enemies… where they had no defense… Our chiefest joy was to see they were mortal, as hoping their death will revive our tranquility.” It’s been estimated that between six hundred and twelve hundred Indians were killed outright in that incident and many more died from wounds and exposure to the elements. History records the occasion as the Great Swamp Fight. About eighty colonial soldiers also died, many from exposure to what was then the harshest winter on record.

Ironically, in the early part of the 20th century, the Rhode Island Society of Colonial Wars erected a large granite monument on the site to commemorate the lives of the brave soldiers who lost their lives in that massacre of Indians. Today, members of the Narragansett, Wampanoag, Nipmuck, and other Indian nations still go to the site to hold ceremonies and make offerings to appease the souls of their departed ancestors. Considerable thought went into portraying this place because of the emotions it can evoke.

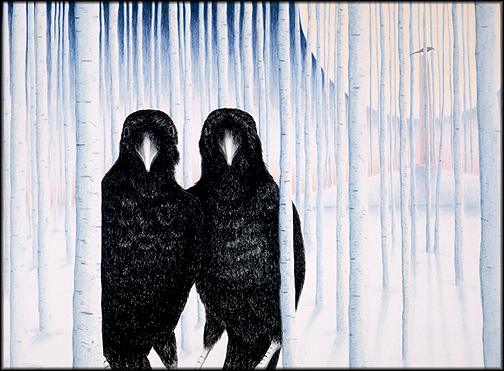

The setting for this painting is a cold December night. Accounts from the period indicate there were three feet of snow on the ground. The granite monument, which still stands today, is visible in the distant landscape. The red glow along the horizon represents the fires of the burning fort. The large sphere in the background symbolizes the combined spirits of those native people who lost their lives in that incident. The trees, devoid of leaves and branches, signify those people who were stripped of everything they owned. The two crows in the foreground are emissaries from the spirit world who have returned to tell the account of what happened there.

The crow was chosen to tell the story for several reasons. Roger Williams, a founding father of the state of Rhode Island, lived with the Narragansett for many years and kept a journal describing his time with them. In one of his accounts he related an old Narragansett legend about the crow. It came from the Southwest, from the gardens of Cautantowwit, their Great Spirit, and brought both a kernel of corn and a bean with it, introducing agriculture to a nomadic people. In this context the crow represents life.

In southern New England Indian mythology, the crow is also associated with the soul. An agent of both good and ill fortune, it commutes between the world of the living and the world of the dead. To a spiritual people, it represents a guide to and from the spirit world.

The crow was also chosen because they are believed to be messengers and birds of great wisdom who know the mysteries of creation. In essence, they are protectors or “Guardians” of this sacred ground. Crows also represent change: they teach us to walk our own path, to speak our own truth, and to know our life’s mission. Here they teach us not to let such things happen again between nations of different peoples.